73. 🗃️ a return to the archive 🗃️

thinking about Weblogistan

Hello, and happy Monday.

Last week was a bit different for all kinds of reasons. Coming off the long weekend, we in the US are now really in! the! holiday! spirit! The lights are up in the trees, it's definitely getting a lot chillier, and it's too real to think that the year is almost over.

I think what made last week particularly special, though, was that it was my first time going back into the archives since the pandemic. More specifically, I went to UC Berkeley's Ethnic Studies Library to take a look at some boxes of student protest flyers. I'll talk more about that below. 🥰

✏️ Still processing.

Although I consider myself an interdisciplinary scholar, I am nonetheless grounded in the historical discipline.

For those of you who don't know that an archive or special collections is, I'll try to give a brief description. Very simply: it's a collection of documents, ephemera, media, or physical objects that are housed in a particular location. Sometimes an individual or institution decides to give their personal papers and items to an archive, which then stores them for future researchers and interested people to one day view. When a library or museum or other institution has "Special Collections," that means that they are one of the places that store these original documents for public viewing. The archives that I look at are usually documents, sometimes media. There was that one time I found a tie in a folder, which was weird but also kind of funny.

I think the reason why I love the archives so much is because I liken them to the way I enjoy and think about paintings. I know it's pretty basic to say this, but one of my favorite artists is Vincent van Gogh. In college, I was lucky enough to study abroad in Paris, and there was this one self portrait by van Gogh that took my breath away:

It wasn't necessarily the composition or the colors or the way everything worked together to produce such vibrancy that had me speechless. It was the way that I could visibly see all the brushstrokes in the thick mounds of paint that covered the canvas. That those brushstrokes implied that there was a hand that painted them so deliberately. The knowledge that connected me to the artist over the span of time from this simple brushstroke.

That's how I feel whenever I see an annotation on a piece of correspondence, or a draft of a typed statement, or a memo written hastily—the curves of the letters slanting forward. It reminds me how very real these people were. It is what grounds me in the work of doing scholarship.

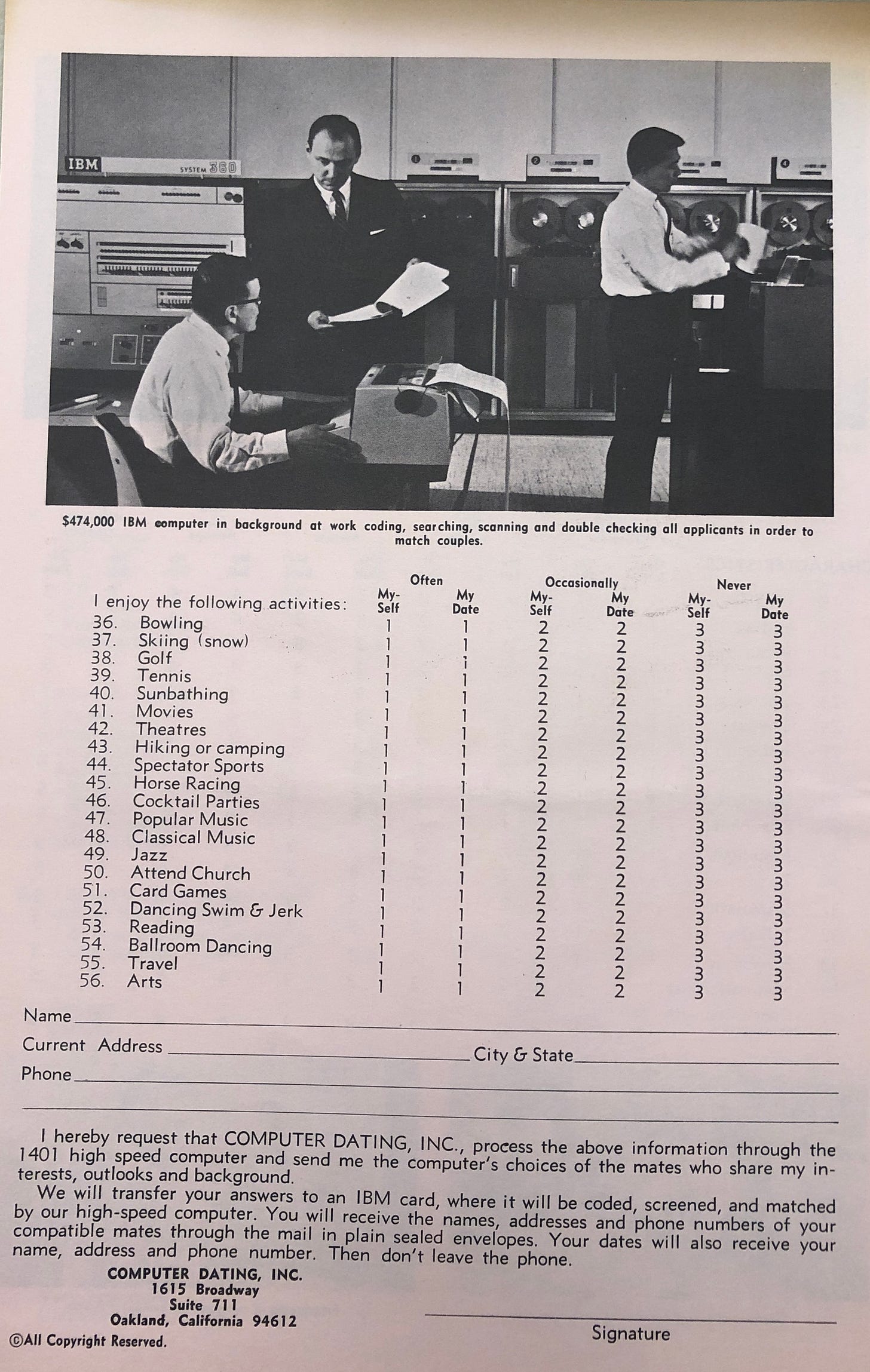

So, imagine my joy upon entering the Ethnic Studies Library to find boxes waiting for me, filled with binders upon binders of campus flyers and pamphlets. I was there to look at some of the HK Yuen collection, which was essentially a collection of Northern California activist ephemera that this one person collected over the course of the 1960s and 1970s. The collection is apparently over three hundred boxes, and I only was able to get through six—it's remarkable to think that this one person was able to compile so many papers over two decades. And the extent of subjects was astounding. Not only were there original pamphlets and flyers from the Black Panther Party and the Anti-Vietnam War Movement, but there was also flyers from the Arab Students Association, the East Wind movement, the SF State strike (Berkeley students set up carpools to the campus!), and so much more. My favorite document, though, had to be the "Computer Dating" pamphlet from 1966, or what I like to think of as the precursor to online dating:

I managed to find some stuff for my own research, too. Pamphlets and flyers from events put on by the Iranian Students Association. These papers and the proper nouns they contained then led me to find other collections that may be potentially helpful for my work. From my process journal:

Even though I haven't yet looked at these collections, I feel excited and hopeful. If anything, it shows me how to dig a little deeper into the things that I find, and not take anything for granted. It always is good to follow potential leads of things I find in the archive.

After over two years of not being in the archives, I can tell you that it felt very good to be back.

📚 Still reading.

Shakhsari, Sima. Politics of Rightful Killng: Civil Society, Gender, and Sexuality in Weblogistan. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

I've wanted to read this book so badly. Many circumstances of the past year didn't allow me the space or time that I thought necessary to read it as closely as I wanted to. And honestly, I felt like I've been waiting to read the book ever since I read their article From Homoerotics of Exile to Homopolitics of Diaspora: Cyberspace, the War on Terror, and the Hypervisible Iranian Queer for my qualifying exams. So, last week was finally the week. Much like when I read Nadia Kim's Imperial Citizens, I felt myself writing in the margins, trying to converse with Shakhsari and ask them evem more questions.

The book's subject matter is concerned with blogging among Iranians inside Iran and in its diaspora during the first decade of the twenty-first century. So much of mainstream media rhetoric around Iranian blogging and the internet during this time was one of hope and change—that the Internet and gives greater connectivity to those inside and outside of Iran, that this is how a regime change will take place within the nation's borders. This assertion, as Shakhsari shows, lacks the nuance and reality of what Iranians on the ground are working toward and for. Rather, much of the blogging in cyberspace reinforces normative dynamics of gender, sexuality, and nationalism that regulates discourse to reflect notions of modern civil society. This ultimately creates a paradox where minoritized poplations—Iranian queer folks and Iranian women, in particular—are both in need of saving and a risk to "international civil society." As they state:

The politics of rightful killing explains the contemporary political situation in the 'war on terror' where those, such as the 'people of Iran,' whose rights and protection are presented as the raison d'être of war, are sanctioned to death and therefore live a pending death exactly because of, andin the name of, those rights...Weblogistan is implicated in the politcs of rightful killing that characterizes the paradoxical situation wherein campaigns for internet freedom exist side by side with deadly economic sanctions. (21, 23)

Shakhsari goes on to show how digital citizenship is actually not in opposition to or subverting the nation-state, but an extension of it and its governmentality. They show how the internet is a site for conflict and inequality that stems from the nation's own forms of excluion and disciplinary action. And this is not just a critique of the Iranian state. When arguing about the Iranian women protester as "simultaneously at risk and risky," they take the argument one step further:

...I suggest that the figure of the Iranian woman protester as para-human is not limiited to her relationship to the Iranian state but concerns the security of the 'international community.' That is, the Iranan woman (protester) as para-human shuttles between the national and the transnational, wherein the 'international civil society' hypervisibilizes her as a 'victim' who neesd to be rescued by the liberating forces (Abu-Lughod, 2013). The hypervisibilization of this figure as both brave and vulnerable legitimizes the securitization of this figure as both brave and vulnerable legitimizes the securitization measure of the 'liberating states, including exclusionary immingration laws. economc sanctions, and ultimately war in the name of the protection of the 'international community.' (110)

The book then examines the role of Weblogistan in maintaining these dynamics, showing how "technologies of digital citizenship reproduce and normalize a classed, gendered, and raced Iranianness in online re-territorizlizations that emphasize individualism and neoliberal ideals of transparency and freedom, all under the rhetoric of 'practicing democracy,'" (114).

There is so much more to unpack in this book, including a particularly illuminating chapter on Iranians in the diaspora who become "experts" for the US during the war on terror. It is both expansive and precise in its breadth; Shakhsari takes on a lot of complicated political and social dynamics in Iran and its diaspora while managing to streamline it effectively for the purposes of their work.

A final note: I am not an anthropologist, so I'm not sure if this is par for the course, but the most significant moments for me where when Shakhsari did autoethnography and shared their own history of internet blogging as well as their relationship to Iran. The ways that they inserted themselves into the text were what made me so deeply moved by the work's arguments, particularly the last story of their sister that is found in the Coda.

🌀 Still consuming.

In the bookshop:

Currently Reading: Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters

On Deck: Wild Seed by Octavia Butler

Shout Your Abortion on Abortion Pills

Robin D.G. Kelley on Cedric Robinson and racial capitalism.

No War, No Sanctions: A Study Group Curriculum to Support Action to Stop War on Iran (from Bay-area based Catalyst Project)

Aside Affects: Digressions on the art and politics of the rhetorical aside

Top books being talked about on reddit in 2021 (organized by subreddit)

📖 Book club corner.

Book club will be taking the month of December off. See you all in January 2022! 🥰

🐶 A pup-date.

Higgins can basically pull of any fashion lewk. It's not hard to guess, then, that he turned on model mode once he had on our friends' pair of cycling sunglasses. Very sporty chic!

As always, thanks so much for reading through, and I'll see you in the next one!

Warmly,

Ida