Hi there! 👋 I’m Ida, and this is tiny driver, a newsletter about research, pedagogy, culture and their intersections. Thank you for being here. Reach out anytime by just hitting reply, I love hearing from you.

Hello, and happy Monday to you all! It snowed here in Chicago over the weekend, so I have mostly been inside watching the flurries outside my window with my boba light* as my writing companion.

As you'll see below, I've been thinking a lot about the importance of scholarly dialogue and debate in the way that disciplines and fields grow and evolve over time. Especially as someone who works in interdisciplinary history, I always consider my work as something that refines our understanding of the past and (more importantly) is built upon the work of the scholars that preceded me. I am not planting a sole flag in uncharted territory—rather, I am offering it up as a way of entering conversations that have been happening long before me.

I first learned this idea of "entering into a conversation" over ten years ago as an undergraduate student, but it wasn't in class. Rather, it happened at a talk I went to on campus that 🤯 BLEW MY LITTLE FIRST-YEAR MIND🤯 .

One day, I was walking through one of the buildings on my campus and saw that a professor named Alison LaCroix was going to give a talk on her book The Ideological Origins of American Federalism. I decided to go. We had spent so much time on the pre-revolutionary era of the US in my AP US History class, that I thought I would be able to understand the talk even though most of it would probably go over my head.

While I can't tell you most of what was said during the talk, what the larger argument of the book was, or what specific scholarly conversations it was speaking to, I can tell you that there was one little bitty part that really stood out to me, and it was about JUDICIAL REVIEW (of all things).

Here's the thing. In high school, it was DRILLED INTO MY LITTLE NOGGIN that the concept of judicial review (or, "the power of courts of law to review the actions of the executive and legislative branches") was established with the US Supreme Court Case Marbury v. Madison. I cannot tell you what the case was about, or what date it was established, but still—over ten years later—I can tell you that the link between JUDICIAL REVIEW and MARBURY V. MADISON were seared into my mind.

So, when LaCroix said that her research argued that judicial review in fact was established PRIOR TO Marbury v. Madison—in effect, COMBUSTING my previous understanding of history as "facts" that are absolutely unchanging—I was FLOORED. (I mean, look at how many CAPITALIZATIONS I am using in this story's retelling!!) I remember that after the talk, I went up to her and was like, "Listen, I'm a first-year. I know nothing, but you just BLEW MY MIND. I learned THIS in school, and now you're telling me that IT MIGHT NOT ACTUALLY BE THAT WAY?!?!?! And you found this out by doing HISTORICAL RESEARCH?!?!" I'm sure that she was very confused by my emphatic tone and overall treatment of her like a f*cking rockstar, but what can I say? It was a wild night for me.

I tell you this story because this talk showed me that all scholarship is a conversation—that research and analysis changes over time, that we are constantly learning more and growing in our understandings of how we got to where we are. The dialectical process continues to move along.

So, imagine my surprise when I read this newsletter post by presidential historian Alexis Coe that comments on Ron Chernow (of Hamilton fame, who wrote that the founding father was an "uncompromising abolitionist") was coming for Jessie Serfilippi, an emerging scholar who published a paper arguing that evidence may point to the fact that Alexander Hamilton did indeed own Black people. An article in the New York Times cites him as saying that Serfilippi is making "bald conclusions" based on her evidence.

As Coe writes in her piece, "Historians aren’t here to present their subjects in the most favorable light, but rather to bring them as fully as possible into the light." And I would add to that that though much of our research is presented as being done alone in our little silos, we are actually in collaboration with each other, through space and time, engaging in years-long and decades-long conversations that should complicate and further our understandings of the past.

*Please see newsletter 26's "Items of Note."

What I teach.

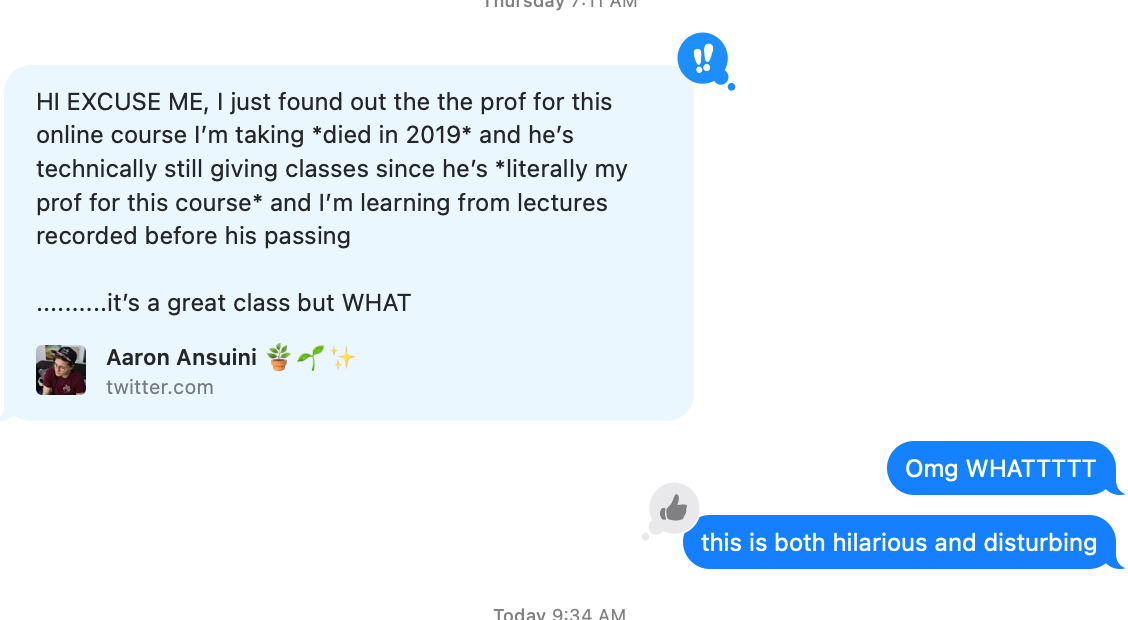

A brief disclaimer: I am not sure what this professor teaches, what institution this is at, or any specifics of the tweet. I only know from the thread that the professor talks about "paintings of snow and horses," which makes me think that this is a course in the humanities. Despite not knowing the full context, I wanted to talk about it because I think it opens up interesting questions about the academy and the importance of research & scholarship alongside teaching.

A couple weeks ago, I had this text exchange with one of my good friends:

Here's the link to the longer thread if you want to read the rest of it:

Given our current circumstances re: the pandemic, online education has been absolutely necessary to the ways in which face-to-face education has been able to adapt. And while I am grateful for this technology, I am a bit apprehensive about what this tweet may be signaling about the future of higher education. Not only is it a bit bleak (and perhaps traumatic) to learn that your professor is, in fact, no longer living from finding their obituary on Google, but it also may signal to our students that knowledge is unchanging. That even from beyond the grave, one is able to teach in the present because what we teach in our courses are unwaveringly canonical. This, however, couldn't be further from the truth.

As I wrote in the disclaimer above, I do not have the full context of this tweet. I do not know the various elements that the institution had to weigh in order to come to decide that this would be the way for the course to be taught. I do not know the extent to which the pandemic and the potential economic implications of it played into this choice. But, I can tell you that it is a bit disappointing to see, considering the number of folks on the already strained academic job market who do not have positions. While many news outlets have talked about this aspect of higher education, I want to instead talk about what this signals to students & how we conceptualize fields of study.

Moreover, from the story with which I started this newsletter, it's clear that one of the most important things that I learned in my undergraduate years was understanding that scholars are participating in a conversation when they conduct research. As I've gone through grad school and started in my first academic position, I've realized how much this informs not only what I teach but how I structure my courses.

I think that this is particularly true for the humanities, perhaps more so than the sciences. In the departments that I have been a part of, there are not many (if any) prerequisites for deciding to take a course. This adds such beautiful variety to the seminars that students are able to take, even when they may not have as much experience in the subject. And even introductory courses such as "Intro to Asian American Studies" or "Intro to Ethnic Studies" can be taught in so many different ways. If we take the latter course title, for instance, it could be organized based on methodology, historiographical chronology, demographics, and on and on. Partly, I think this has to do with the particular expertise that an instructor might bring to that field. And partly, I think this has to do with the changes in the ways that we now conceptualize the field. In the present day, I could see this course engaging with Arab American Studies for example, something I think would not have been so common in the past. In essence, what I'm trying to say is the field and the conversations at the research level are ever-evolving, and that definitely informs what we teach and how we teach it.

By creating a situation in which students are learning from a colleague who has passed, then, it makes it seem as though these fields are not engaging in ever-growing conversations, and that there is a fixed way and to acquire knowledge. Part of the joy of teaching a course (and then teaching it over again) is the chance I have to revise the course design in a way that reflects the changing contours both of the field writ large and my own evolution in thinking. To say that the courses I teach is identical in its iterations would be deeply untrue.

This is an aspect of academic research that I think it is important to communicate with students. I often say that I cannot always promise answers, but I can promise more questions, as that to me is the spirit of historical inquiry, as well as the humanities & social sciences more broadly.

What I consume.

In the Bookshop:

Currently Reading: Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

On Deck: Juliet the Maniac by Juliet Escoria

Item(s) of note.

Please see above re: my ideal day-to-day.

A visual guide on the many, many ways that we can contribute to social change. (h/t Nisha Mody)

A helpful list of productivity tools from Luke Leighfield.

A dictionary of color combinations.

Sometimes I forget that there is art in the world that I hopefully will get to see in person sometime.

A pup-date.

Girlie's all tongue today:

As always, thanks so much for reading through, and I'll see you in the next one!

Warmly,

Ida

✨✨ The best way to reach new readers is word of mouth. If you click THIS LINK, it’ll create an easy-to-send, pre-written email you can just fire off to some friends. ✨✨

tiny driver is a labor of love—one that involves a lot of caffeine. If you find the newsletter joyful and/or useful, consider supporting me & my work so I can invest more into the future of the newsletter! Every little bit helps!

Right now, there are two ways to support tiny driver:

You can buy me a coffee.

You can buy books through the tiny driver Bookshop! With each purchase made from the books in my "shop" (as well as what I link to in the newsletter), a small portion of the purchase is given to tiny driver through Bookshop's affiliate program.

If you liked this post, why not subscribe? 🥰

I love this! "Scholarship as Conversation" is part of the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education by the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL). I also see your nod to "Research as Inquiry"! http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

It's so true that we bring ourselves into any teaching opportunity, and that's totally based on where we are at in the moment. I appreciate this, and I'm going to share with colleagues! And thanks for the shout out <3

Hi Ida! This line you wrote caught my eye, “ And I would add to that that though much of our research is presented as being done alone in our little silos, we are actually in collaboration with each other, through space and time, engaging in years-long and decades-long conversations that should complicate and further our understandings of the past.”

I especially appreciate the part about how these conversations *should* complicate our understanding. I’m not an academic but a reader of research (and articles about research) and so often it seems like it’s being presented as “this research solves X”. Basically the goal is usually the opposite of complicating matters. But I think that misses the point, complications are how we move the conversation in interesting directions to hopefully impact change. Resisting complications could even be dangerous if we’re too locked in on a simple outcome that we ignore what is or could be.

OK, not sure if that makes sense. Hah. Thanks for sharing this newsletter! I always walk away with something to think about after reading tiny driver.